Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) represents a fundamental reorganization of state-citizen interaction through interoperable digital systems for identification, payments, and data exchange. While current governance models emphasize technical security (cryptographic protocols, Private Enhancing Technologies, or PETs) and operational accountability (oversight mechanisms, transparency requirements), they suffer from a critical temporal blind spot—failure to account for political ruptures, authoritarian reversals, and systemic accountability challenges. This brief introduces justice readiness as an essential third layer of trust, complementing existing technical and governance trust layers to ensure that digital infrastructures remain credible and actionable across political transitions. Justice readiness transforms DPIs from technocratic tools into constitutional safeguards for truth-telling, reparations, and accountability. Justice readiness encompasses three pillars:

1. Narrative Integrity: Tamper-proof preservation of context-rich records through cryptographic immutability and trusted execution environments

2. Evidence Admissibility: Forensic-grade data usability in legal proceedings via standardized legal APIs and chain-of-custody protocols

3. Legitimacy Maintenance: Institutional and technical safeguards against political capture through multi-stakeholder cryptographic governance

In this brief we provide a comprehensive techno-legal blueprint for implementation, analyze major DPIs through this justice-ready lens, and propose a sequenced pathway for global adoption through multilateral institutions. Without this third layer, DPIs risk becoming instruments of impunity rather than pillars of accountable governance, particularly as AI integration increases system complexity and opacity (Zuboff, 2019; WEF, 2022).

Key Takeaways

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) has emerged as the foundational layer of digital governance, comprising digital identification systems (e.g., India's Aadhaar, Estonia's e-ID), payment platforms (e.g., UPI, Brazil's PIX), and data exchange mechanisms (e.g., X-Road, India's Account Aggregator framework) that enable efficient service delivery at scale (World Bank, 2021; UNDP, 2022). The rapid global deployment of DPIs represents what Mann and Daly (2022) term "the material constitution of digital statehood"—a fundamental rearchitecting of how states organize and exercise power.

Current DPI governance models retain a temporal blind spot. Frameworks such as the OECD (2023) and the World Bank’s GovTech Maturity Index (2021) prioritize technical security and operational accountability within assumed stable political contexts. They are designed for the purpose of continuity of administration while neglecting continuity of accountability across political transitions.

The consequences of this blind spot become apparent during periods of crisis or political transformation. DPIs designed for service delivery frequently fail when called upon to support truth commissions, human rights investigations, or mass claims adjudication. Truth commissions have historically struggled with fragile archives and contested evidentiary systems (Hayner, 2010), while reparations programs depend on registries that are vulnerable to manipulation or collapse (de Greiff, 2006). In South Africa, biometric infrastructures built for one political purpose later became obstacles to justice in subsequent regimes (Breckenridge, 2014).

Transitional justice mechanisms (truth commissions, reparations programs, and hybrid or special tribunals) seek to uncover truth, repair harm, and hold perpetrators accountable. Yet, they frequently operate under fragile institutional conditions where archives are dispersed, registries contested, and evidence vulnerable to erasure. These weaknesses are infrastructural as well as political. Justice-ready DPI can provide the durability, verifiability, and survivor-centered access that transitional justice processes require.

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Tunisia’s Truth and Dignity Commission both depended on dispersed, paper-based testimony archives. These records proved vulnerable to tampering, loss, and political interference (Hayner, 2010). A justice-ready DPI, anchored in cryptographic immutability and enriched metadata standards, could have preserved witness statements as tamper-evident archives. This would ensure their survival as collective memory even after political turnover. Such an infrastructure would have also reduced opportunities for revisionism while enhancing the long-term evidentiary value of testimony.

Reparations schemes often hinge on accurate registries of victims and claims, yet errors and exclusion are common. Peru’s Registro Único de Víctimas and Colombia’s reparations registry illustrate these challenges: both suffered from duplicate claims, verification problems, and political contestation that undermined credibility (de Greiff, 2006; Daly & Sarkin, 2007). A justice-ready DPI could embed legal-grade chain-of-custody protocols and consent-based access mechanisms, preventing fraud, ensuring consistent adjudication, and giving survivors secure, ongoing access to their own records regardless of regime change.

Courts such as the Special Court for Sierra Leone and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia have faced recurring challenges authenticating digital evidence gathered under contested conditions (Sikkink, 2011; Daly & Sarkin, 2007). Without standardized evidentiary protocols, questions about provenance have weakened prosecutorial effectiveness and public legitimacy (ICC, 2019). A justice-ready DPI could mitigate this risk by producing standardized digital evidence packages with verifiable provenance, supported by legal APIs, to ensure admissibility across jurisdictions and preserve probative value over time.

Taken together, these examples highlight a structural lesson: transitional justice mechanisms falter not only because of political resistance but also because of infrastructural fragility. Justice-ready DPI offers a way to institutionalize truth-telling, reparations, and accountability into the architecture of digital governance, making these processes more durable, credible, and resistant to capture.

To make DPIs resilient against political rupture, trust must extend beyond technical reliability and institutional oversight. A comprehensive trust model for DPI must thus address three distinct dimensions.

The foundational layer addressing system reliability, security, and privacy through cryptographic protocols (SHA-256, zero-knowledge proofs), privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs), and cybersecurity measures (Nissenbaum, 2009; Zuboff, 2019; Reed, 2021; Lindell, 2020). This layer mitigates risks of technical failure and external attacks.

The institutional layer addressing legitimate operation through oversight mechanisms, transparency requirements, algorithmic impact assessments, and redress systems (Barocas et al., 2019; O'Neil, 2016; OECD, 2014). This layer mitigates risks of misuse by authorized operators.

The temporal and contingency layer ensuring DPIs remain credible and actionable across political transformations. This layer mitigates risks of historical erasure, evidence suppression, and institutional capture.

This third layer extends the normative reach of transitional justice—truth, accountability, and institutional continuity—into the digital domain.

The three pillars of justice readiness (1) narrative integrity, (2) evidence admissibility, and (3) legitimacy maintenance resonate with core normative anchors of transitional justice and can serve as their digital instantiation across political transitions. Each is both a technical safeguard and an infrastructural translation of established legal norms.

Narrative integrity operationalizes the right to truth, a principle enshrined in the UN’s Joinet/Orentlicher Principles (UNHRC, 2005). Transitional justice scholarship has long emphasized truth-telling as both a moral imperative and a legal right (Teitel, 2000). By embedding cryptographic immutability and context-rich metadata into DPI, testimony and archives can be preserved as tamper-evident and contextually robust records. Such infrastructures curtail revisionism, protect against erasure by hostile regimes, and ensure that collective memory remains intact across political ruptures.

Reliable evidence is the foundation of prosecutions, vetting processes, and reparations claims. As Vinjamuri and Snyder (2004) note, the legitimacy of transitional justice institutions often hinges on the robustness of their evidentiary base. Justice-ready DPI can meet this requirement by embedding forensic-grade chain-of-custody protocols, trusted execution environments, and standardized legal APIs that align with international evidentiary thresholds, including those of the International Criminal Court (ICC, 2002). In this way, DPI functions not only as a platform for service delivery but as an evidentiary safeguard.

Post-conflict and post-authoritarian contexts are marked by institutional fragility, where commissions, registries, and tribunals are vulnerable to collapse or capture (Vinjamuri & Snyder, 2004). Multi-stakeholder cryptographic governance mechanisms, such as threshold signatures and secure multi-party computation, can distribute authority across independent actors, embedding structural safeguards against unilateral manipulation. These measures ensure that critical registries and decision systems remain resilient even amid regime change.

Taken together, the three pillars demonstrate how digital infrastructures can embody the normative foundations of transitional justice. They render the right to truth, accountability, and institutional continuity not only political aspirations but enforceable design features of DPI, ensuring that justice remains viable in the face of political upheaval.

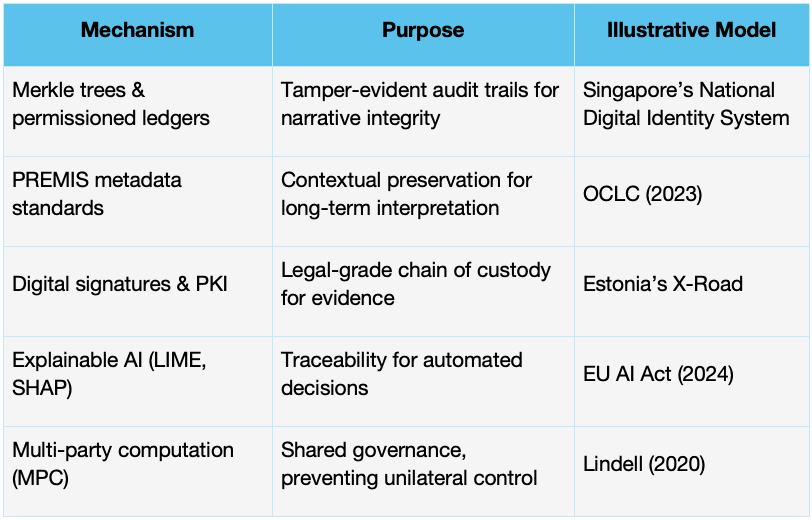

Justice readiness can be engineered through interoperable safeguards that reinforce each other across governance layers. Below we lay out a blueprint including different mechanisms.

Cryptographic immutability, context-rich metadata, and trusted execution environments form the backbone of narrative integrity in justice-ready DPI. Merkle trees and permissioned ledgers generate tamper-evident audit trails that preserve data integrity even under political pressure, as demonstrated by Singapore’s National Digital Identity system, which employs cryptographic chaining to secure citizen transaction records (Reed, 2021).

Complementing this, the PREMIS (Preservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies) standard ensures systematic capture of contextual information—such as provenance, access rights, and preservation activities—so that records remain interpretable and verifiable over time (OCLC, 2023).

Finally, trusted execution environments (TEEs), including Intel SGX and AMD SEV, enable sensitive data to be processed within secure enclaves, protecting against system-level vulnerabilities and insider manipulation (Sabt et al., 2015).

Admissibility mechanisms ensure DPI records meet cross-jurisdictional forensic and legal standards. Legal-grade chain-of-custody protocols, built on digital signatures and Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), create non-repudiable access logs that align with international evidentiary requirements; Estonia’s X-Road system illustrates this approach by maintaining cryptographically verifiable logs of all data exchanges (ICC, 2019).

Standardized legal APIs, such as those based on LegalXML Electronic Court Filing (ECF), further safeguard evidentiary integrity by enabling interoperable evidence packages that retain their probative value across courts and administrative systems.

To ensure durability over time, long-term digital preservation strategies—including format migration, emulation, and the adoption of quantum-resistant cryptographic pathways—are essential for maintaining evidentiary usability across successive technological transitions.

Legitimacy and AI safety mechanisms ensure that DPI remains credible and resilient even as automated decision-making becomes more deeply embedded in governance. Algorithmic accountability frameworks require the preservation of detailed audit trails—including model versions, training data provenance, hyperparameters, and decision logs—so that system decisions can be reconstructed and verified; the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (2024) already mandates such documentation for high-risk systems (WEF, 2022; CNIL, 2023).

Explainability by design, using techniques such as LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations), strengthens transparency by providing interpretable reasons for automated outputs (Adadi & Berrada, 2018).

Finally, multi-stakeholder cryptographic governance mechanisms, such as multi-party computation (MPC) and threshold signatures, distribute authority across independent entities, ensuring that no single actor can unilaterally alter or capture critical system functions (Lindell, 2020).

Brazil's online dispute resolution platform demonstrates partial alignment with justice readiness principles. The system maintains immutable records of consumer complaints and integrates with judicial systems, showing strong narrative integrity and evidence admissibility (de Azevedo Cunha, 2021). Legitimacy maintenance remains weak: effectiveness fluctuates with administrative priorities.

France's federated digital identity system excels in legitimacy maintenance through independent oversight by CNIL and operation under the eIDAS regulatory framework (CNIL, 2023). Yet it is designed for authentication rather than preservation, creating a narrative-integrity deficit.

India's biometric identification system illustrates the tension between technical capability and political legitimacy. While Aadhaar authentication logs possess evidentiary value, the system suffers from a profound legitimacy deficit due to well-documented exclusion errors and surveillance concerns (Khera, 2019).

Mainstreaming justice readiness faces entrenched political and institutional barriers. Foremost, sovereignty concerns loom large. States with fragile rule-of-law traditions may perceive justice-ready DPI as a latent threat. DPI may be seen as an infrastructure that could later expose elite actors to prosecution or public scrutiny. Such fears could generate resistance at multilateral venues like the UN, OECD, or World Bank, where consensus is required for norm diffusion (Paris, 2004).

Institutional risk aversion compounds this reluctance. Development institutions are oriented toward efficiency, inclusion, and growth metrics. Justice-oriented safeguards—particularly those anticipating regime change or state crimes, can appear politically destabilizing and beyond institutional mandates (Merry, 2006).

Resource asymmetries further threaten uptake. Low- and middle-income states often lack the technical capacity, legal expertise, and fiscal space to implement justice-readiness features. Without targeted financing, technical assistance, and phased adoption models, the approach risks exacerbating existing digital inequalities (World Bank, 2021).

Finally, the governance ecosystem is fragmented. DPI standards are dispersed across ISO, IEEE, W3C, ITU, and various UN agencies. Embedding justice readiness will require sustained coordination and incentives to align these disparate regulatory and funding bodies—a task that demands strong coalitions of states, civil society, and epistemic communities (OECD, 2014).

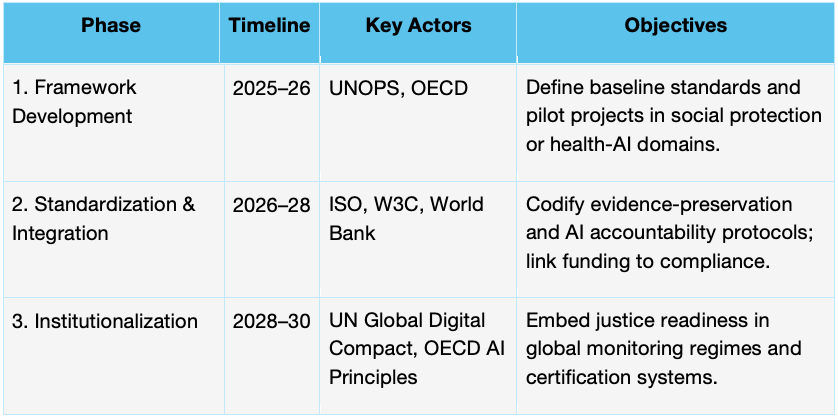

These challenges do not preclude adoption but make sequencing essential. A phased approach can align incentives, reduce perceived risks, and build momentum, see table below.

Phase 1: Evidence and Framework Development (2025–26).

UNOPS and OECD working groups should draft baseline standards for justice-ready DPI, while pilot projects in social protection and health-AI domains demonstrate feasibility (OECD, 2023; UNDP, 2022). Early, domain-specific pilots reduce institutional risk aversion by showing that justice safeguards strengthen resilience without undermining service delivery.

Phase 2: Standardization and Integration (2026–28).

Formal engagement with ISO, IEEE, and W3C can codify technical standards for digital evidence preservation and AI accountability. In parallel, embedding justice-readiness indicators into World Bank and UNDP funding assessments ensures that financing incentives reinforce adoption. This phase addresses fragmented governance by creating shared benchmarks across institutions.

Phase 3: Institutionalization and Global Uptake (2028–30).

For durable legitimacy, justice readiness should be anchored in global compacts and monitoring regimes. Integration into the UN Global Digital Compact and OECD AI Principles, backed by an independent certification body, would provide normative authority. A multi-donor technical assistance facility can reduce capacity gaps and frame adoption as cooperative burden-sharing rather than unilateral imposition.

Taken together, this sequenced strategy provides a realistic pathway from principle to practice. By addressing sovereignty concerns, institutional mandates, resource asymmetries, and governance fragmentation in turn, it situates justice readiness not as an aspirational ideal but as an implementable component of global DPI governance.

The global turn toward AI-governed systems raises urgent questions of legitimacy, bias, and accountability. Without justice-ready design, the infrastructures of digital governance could replicate historical impunity under new technical guises.

By contrast, embedding cryptographic integrity, forensic-grade evidence, and multi-stakeholder oversight ensures that digital statehood supports democratic values even amid disruption. This aligns with ongoing efforts such as the UN Global Digital Compact, OECD AI Principles, and WEF Governance of AI initiatives.

Justice readiness thus bridges the gap between digital trust and democratic resilience.

Justice readiness is not a theoretical luxury but a practical necessity for digital sovereignty. By embedding cryptographic integrity, forensic admissibility, and institutional resilience into the architecture of DPI, states can ensure that these infrastructures function not only as platforms for service delivery but also as durable guarantors of accountability.

The argument advanced here reframes DPI from a purely technocratic project to one with constitutional implications. Without a third layer of trust, DPIs risk entrenching impunity by preserving only administrative continuity while leaving justice vulnerable to political rupture (Mann & Daly, 2022). With justice readiness, however, they can provide structural guarantees for truth-telling, reparations, and institutional legitimacy even under conditions of authoritarian reversal or systemic crisis.

Justice readiness reframes digital public infrastructure as a constitutional technology—one that encodes the right to truth, accountability, and institutional continuity into the very fabric of governance.

This brief has outlined both a normative justification and a techno-legal blueprint for operationalizing justice readiness. The proposed phased pathway demonstrates that adoption is possible despite sovereignty anxieties, institutional risk aversion, and resource asymmetries. Sequenced pilots, standardization, and institutionalization can move justice readiness from concept to practice within the next decade. The policy implication is clear: global governance actors must recognize that resilience in digital infrastructure is inseparable from resilience in democratic institutions. Architecting for contingency is not simply about technical robustness; it is about embedding the right to truth, accountability, and institutional continuity into the very fabric of digital governance. The time to act is now, before the next crisis determines whether DPI serves justice—or impunity.

Dr. Arnaud Kurze is a Senior Fellow in GGI’s AI Governance Programme, Associate Professor of Justice Studies at Montclair State University (US), and Director of Project AROS Lab, an experiential learning platform advancing digital literacy and innovation.

Dr. Adriana Banozic-Tang is a Member of the United Nations Digital Public Infrastructure Safeguards Workgroup and Adjunct Faculty at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.